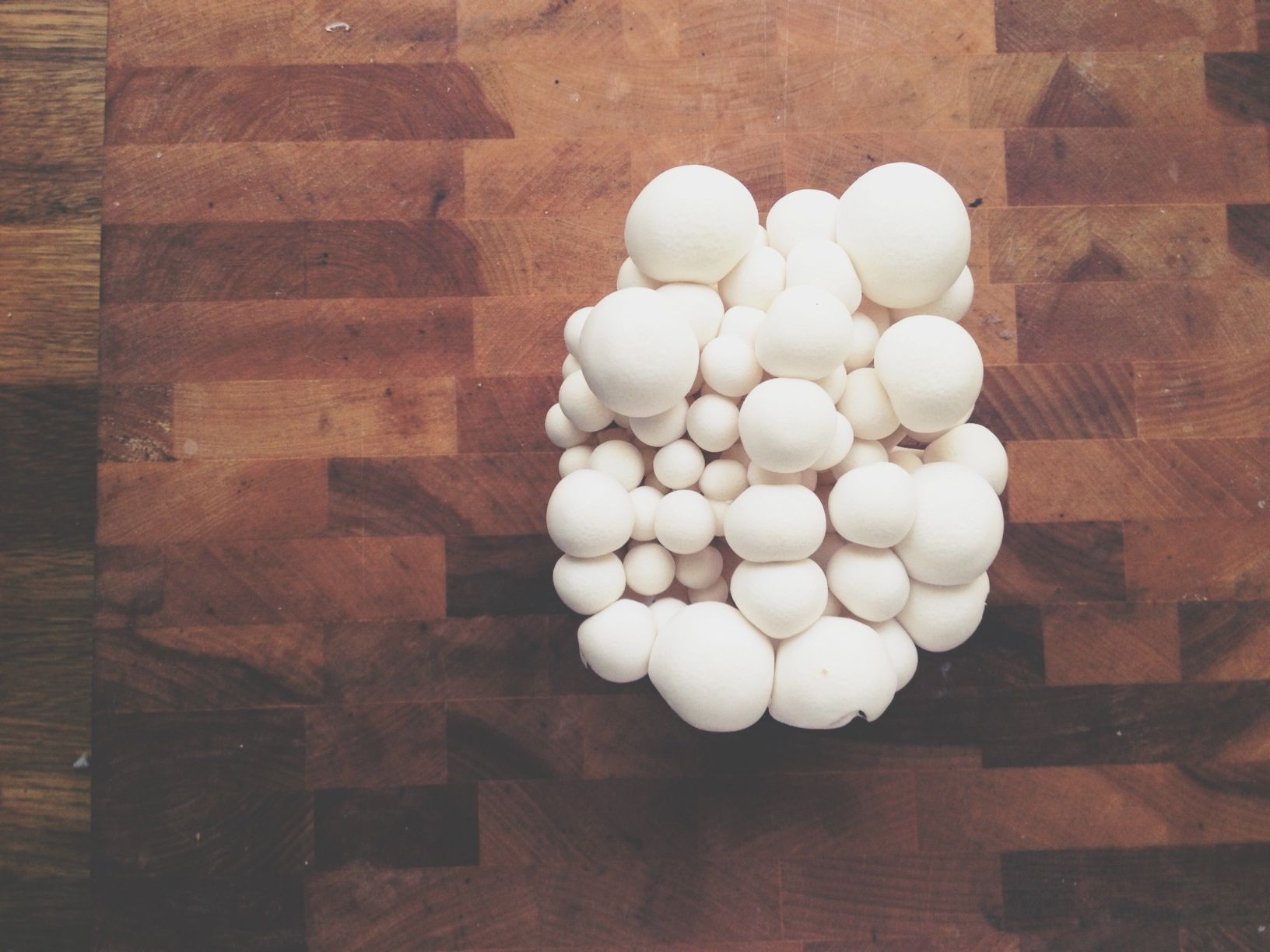

When you rinse beans in a colander and rustle them with you hand, they sound like pebbles collected from a rocky beach.

That's one reason why I love cooking with beans, the gentle sound they make. Some other more practical- and nutritionally-based reasons are that they're good for you, creamy on the inside, and are easy to make and freeze for later. If I have cooked beans in the house, I know a decent meal is always achievable. So I've been making a lot of beans this month, from garbanzo beans for hummus to black and pinto beans for chili. All beans have been welcome.

Sunshine, also, has been welcome, although its abundance is an embarrassment of riches given the circumstances in other parts of the country. I'm not one to complain about the heat of winter. In California, it's a constant reminder of how good we have it, but with all the 75-degree weather we've been having (sorry, East Coast folks!), I've been craving cold. Not too much, of course, but a weekend of good, consistent rain would make me very happy. (I prefer rain on Saturdays when I can stay at home and enjoy it, not when I have to get on the freeway and drive to work.)

I always watch Hello, Dolly when it rains. And I make soup. But so far, there hasn't been a good day for this, so all the parasols and parades and musical numbers will have to wait until the mood strikes. Aside from failing to watch a favorite movie, the constant warm weather is also causing drought and fire, two things we're far too familiar with in California and that a good dose of rain could help quell. But I can't avoid soup for too long, even when it's warm, so I've been making a series of stews with meat or grains or beans that lend a bit of heft and offer up profound satisfaction.

That's January so far. Sunshine, beans, stews, and re-reading Jane Hirshfield's After. Reading a poetry collection by Jane Hirshfield is like standing on the edge of a mountain and letting your face absorb the wind. Her poems just resonate. They always make you feel something, usually more than one thing, and make you think and question long after the book has been placed back on the shelf. That's been my experience, anyway. This poem, in particular, seemed well suited for a discussion of beans in the new year.

Two Washings

by Jane Hirshfield

One morning in a strange bathroom

a woman tries again and again to wash the sleep

from her eyelids' corners,

until she understands. Ah, she thinks, it begins.

Then goes to put on the soup,

first rerinsing the beans, then lifting the cast-iron pot

back onto the stove with two steadying hands.

From After, Harper Perennial, 2006

It's remarkable how much we can learn of this woman in seven lines. The fact that she's in a strange bathroom is telling, and points to an upheaval of some kind. But she's not in a hotel or on vacation escaping, because unless she's rented a little flat with a kitchen and gone to the market, she wouldn't be rinsing beans before the sun comes up. She must be staying with someone. A friend, more than a friend, a family member. Wherever she is, she is trying to steady her hands again. Two washings for the beans, two for the spirit.

Barley, Bean and Mustard Greens Stew

Recipe adapted from Bon Appetit

A photo of this soup occupied a full page in the January issue of Bon Appetit, and I dog-eared it immediately. The original recipe uses spelt, but since I had a mason jar full of barley in the pantry, I made a simple substitution. Farro would also do nicely here. I reduced the red pepper flakes from 3/4 teaspoon to 1/2 teaspoon and felt that the soup had plenty of spice, so modify this to your liking.

1 medium onion, chopped

1 small fennel bulb, cored and chopped

1 carrot, chopped

1 celery stalk, chopped

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, plus more for serving

1 cup barley

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon tomato paste

1/2 teaspoon crushed red pepper flakes

12 cups vegetable stock

1/2 head escarole, leaves torn into pieces

2 cups cooked cannellini or navy beans

Parmesan cheese, for serving

Dump the onion, fennel, carrot and celery into the bowl of a food processor and pulse until finely chopped. Heat the oil in a large stock pot over medium heat. Add the barley and cook, stirring often, until the grains are slightly browned and smell fragrant, about 3 minutes.

Add the vegetables and season with a generous pinch of salt and pepper. Cook, stirring occasionally, until vegetables are softened, about 6 to 8 minutes. Add the tomato paste and red pepper flakes, and cook until the paste is well-incorporated, about 1 minute.

Pour the broth into the pot and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer, partially covered, until the barley is tender, about 20 to 40 minutes, depending on the grain. Stir in escarole and beans and cook for another 3 to 4 minutes, or until the escarole is wilted and the beans have warmed through. Serve drizzled with additional oil and topped with Parmesan shavings.